Inertia of the Real

About the Exhibition

March 26 - April 2, 2021 - Gillespie Gallery, George Mason University

This exhibition features a collection of recent work by Jorge E. Bañales in which the artist uses writing, photography, collage, music and video to investigate the mental and physical topography of late capitalism. The works, via the practice of psychogeography, concentrate mostly on the site of the former Landover Mall in Landover, Maryland and how the heterotopic and hauntological abandoned suburban space, and more specifically the dilapidated structure that of the mall’s logo, now stripped of its imaginary and symbolic meaning, can activate an experience of the Real.

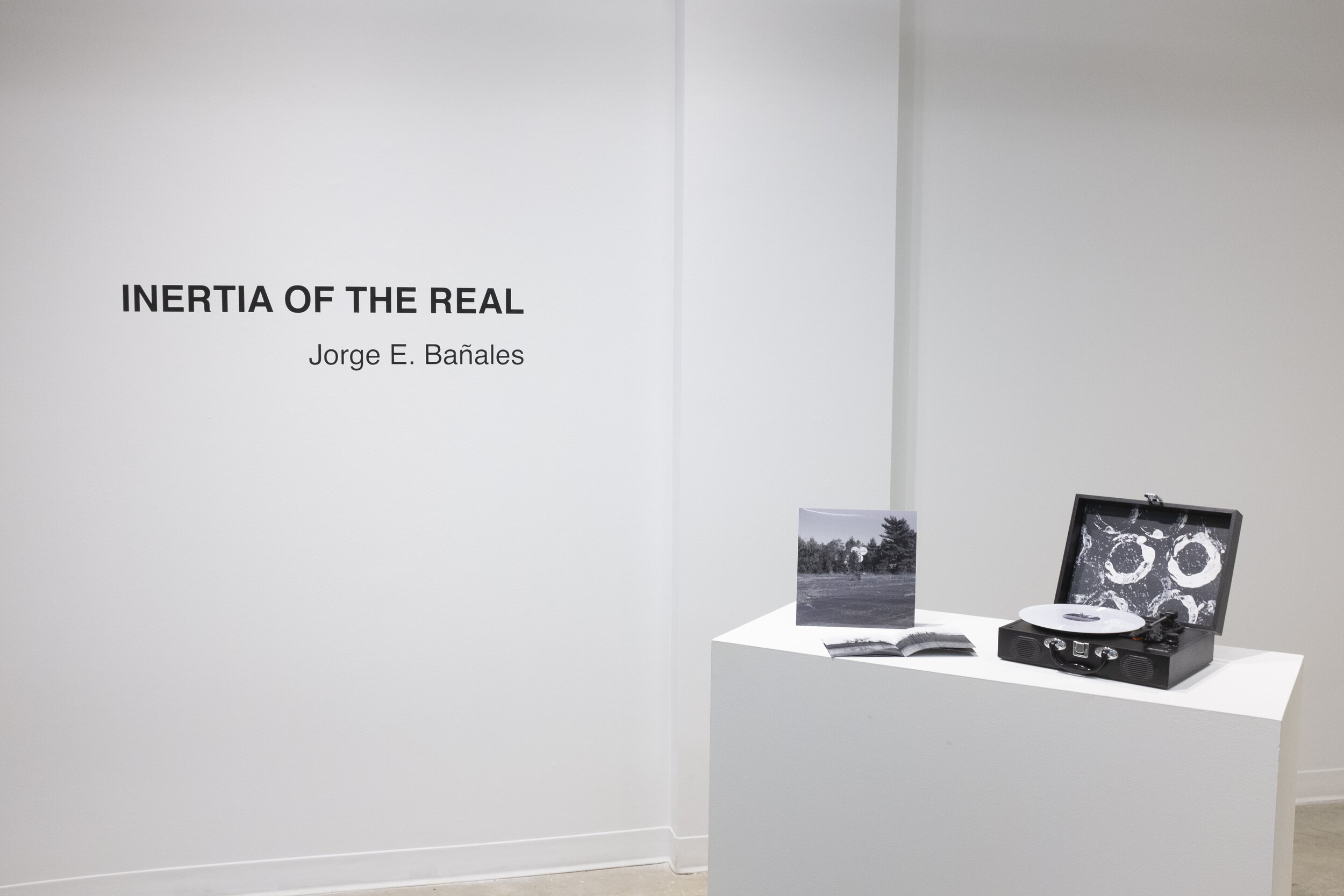

INNER LOOP OUTER LOOP (Vinyl Record)

".. 'non-places' - the generic zones of transit (retail parks, airports) which will come to increasingly dominate the spaces of late capitalism."

“...the sound of cars is locked into a looped drone."

“Ghosts of My Life. Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures,” Mark Fisher, 2014, page 5.

Field recording of a parking lot at the former Landover Mall, Landover, Maryland. The sounds of Capital Beltway traffic, birds, insects and the wind, were recorded digitally a few hundred feet from one of the few remaining structures at the site: what used to be the neon lit logo and advertising sign of the shopping center. Vinyl record, 2019.

Images from the booklet taken with a medium format camera.

Further reading:

https://dj.dancecult.net/index.php/dancecult/article/view/378/391

Inertia of the Real

“Capitalism is all the time in crisis. This is precisely why it appears almost indestructible. Crisis is not its obstacle. It is what pushes it forwards towards self-revolutionizing, permanent, extended self-reproduction – always new products. The other invisible side of it is waste, tremendous amount of waste.

We shouldn’t react to these heaps of waste by trying to somehow get rid of it. Maybe the first thing to do is to accept this waste. To accept that there are things out there that serve nothing. To break out of this eternal cycle of functioning.

The German philosopher Walter Benjamin said something very big. He said that we experience history, ‘what does it mean for us to be historical beings’, not when we are engaged in things, when things move, only when we see this, again, rest waste of culture being half retaken by nature, at that point we get an intuition of what history means.”

“We see the devastated human environment, half empty factories, machines falling apart, half empty stores. What we experience at this moment, the psychoanalytic term for it would have been the ‘inertia of the real’; this mute presence beyond meaning.

“The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology,” Slavoj Žižek, 2012

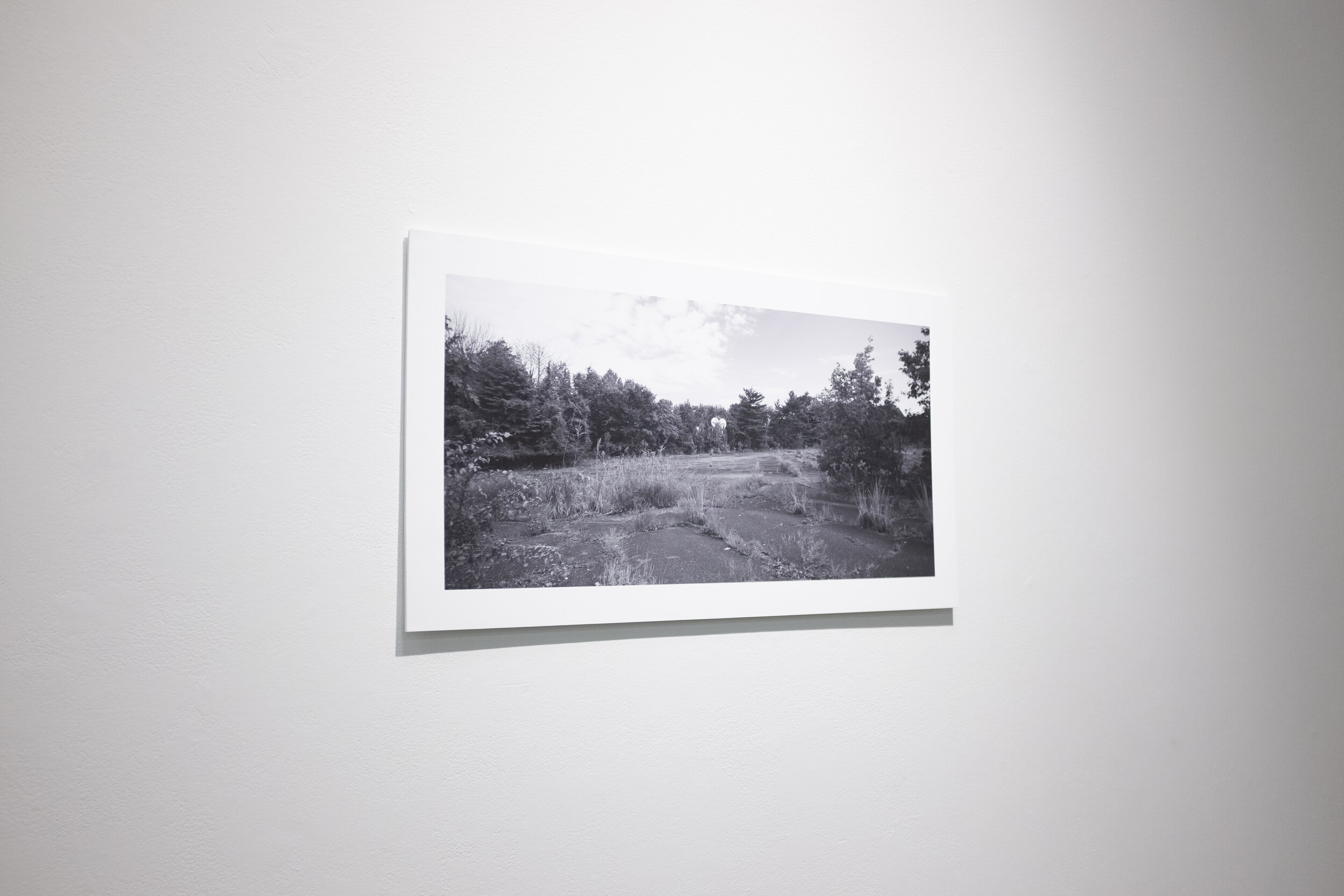

A composite of three photos taken with a tilt-shift lens of one of the smallest parking lots, and one of the few remaining structures at the now extinct Landover Mall, Landover, Maryland. 28 x 15 inches, inkjet print, 2018.

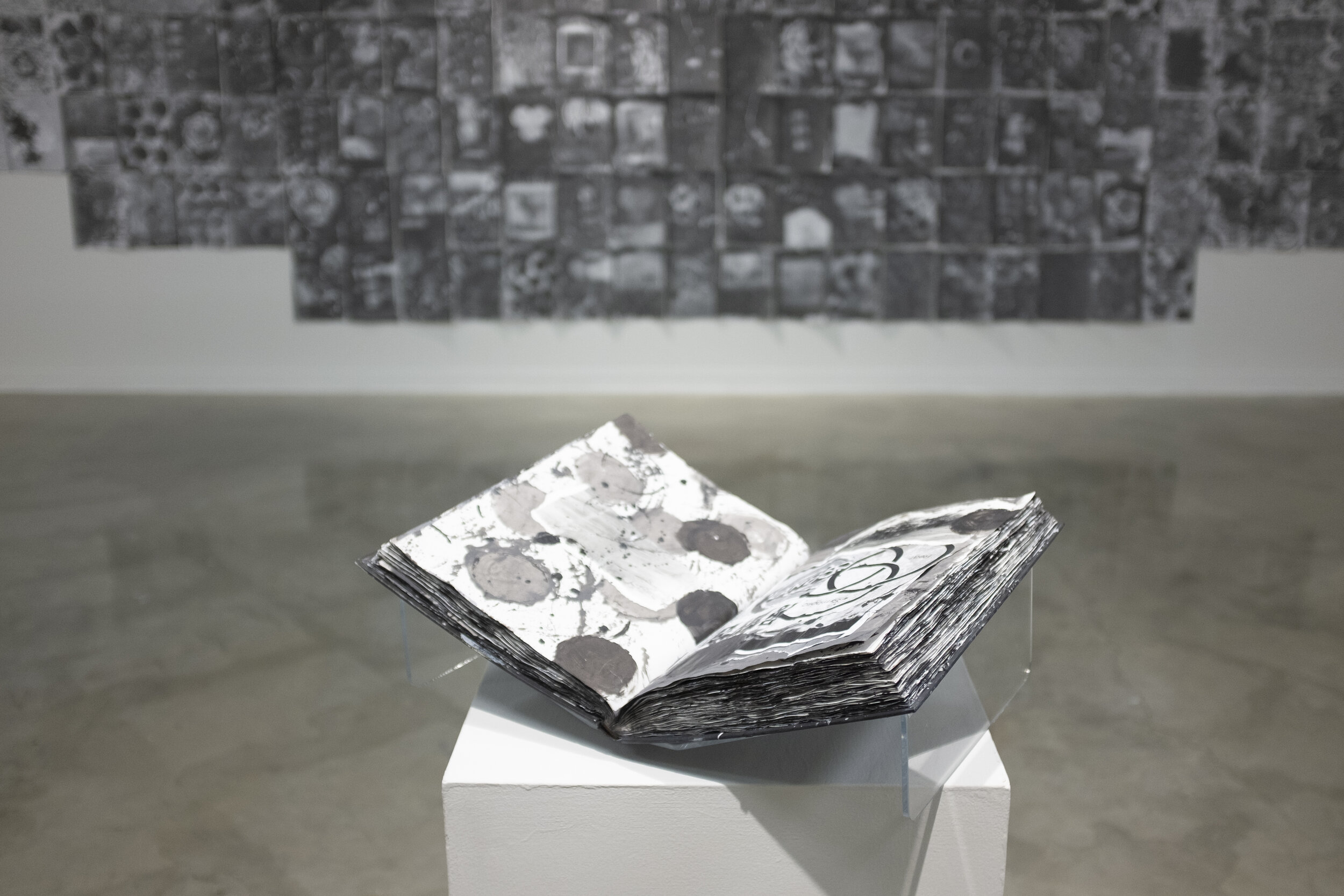

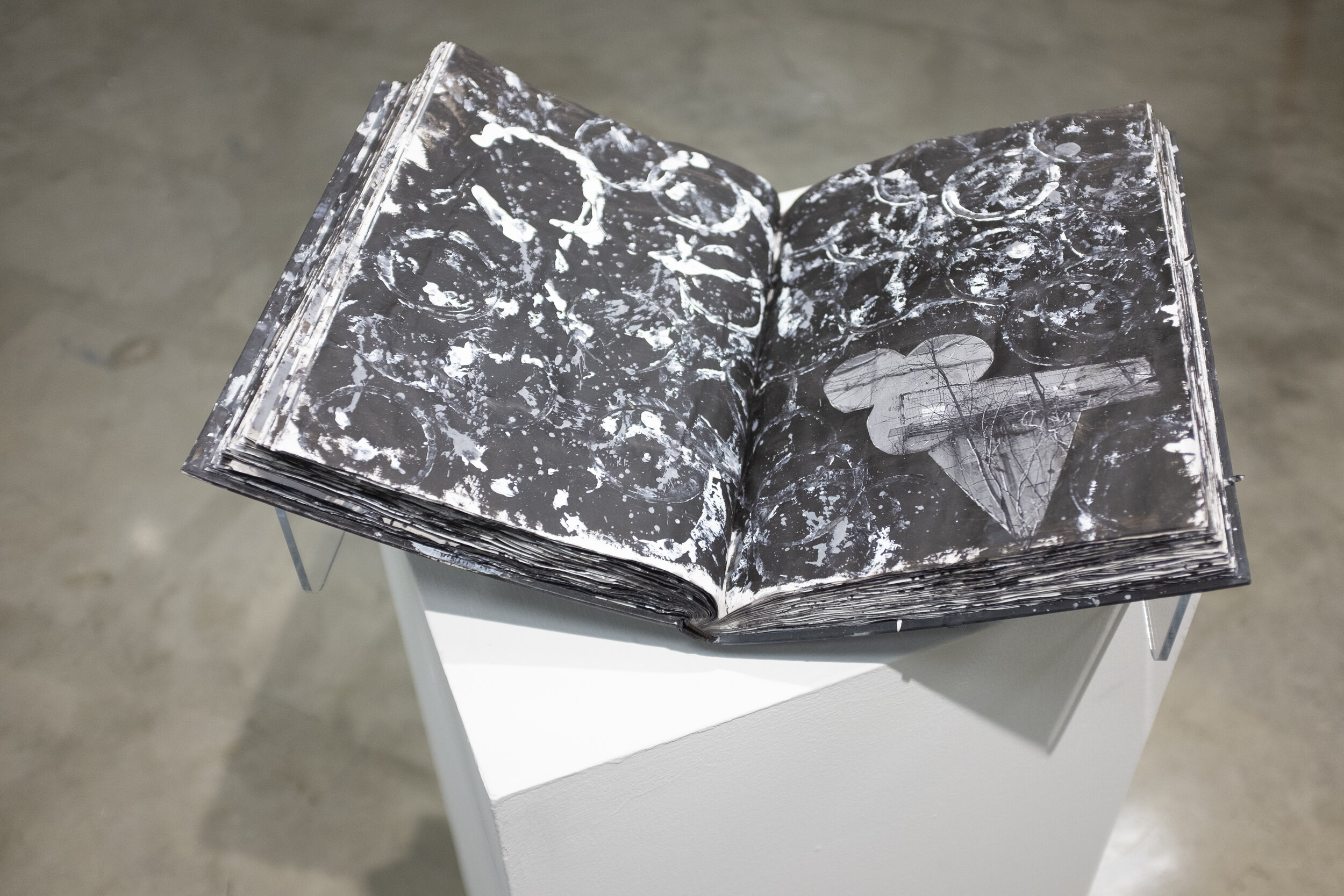

Imaginary Symbolic Real

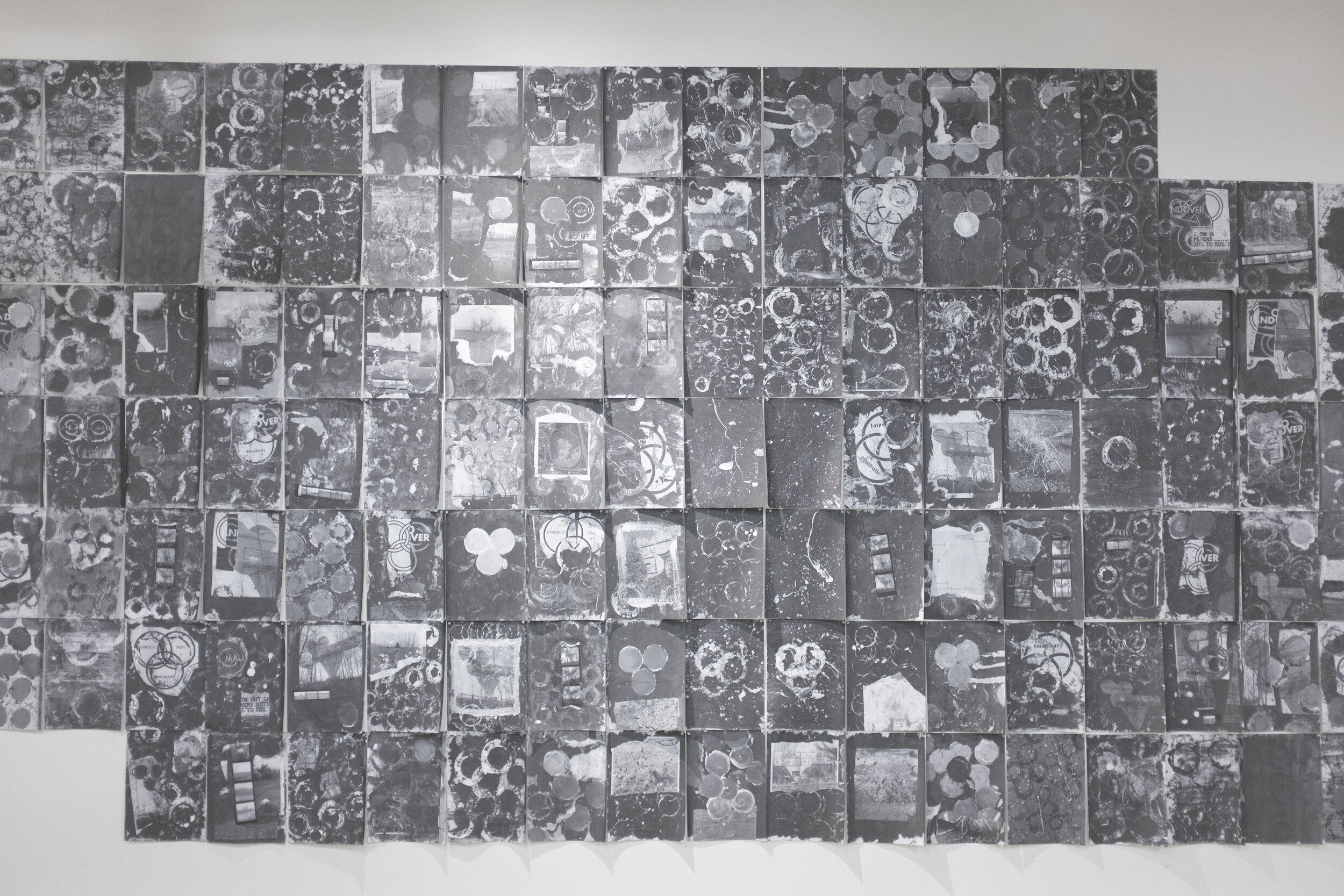

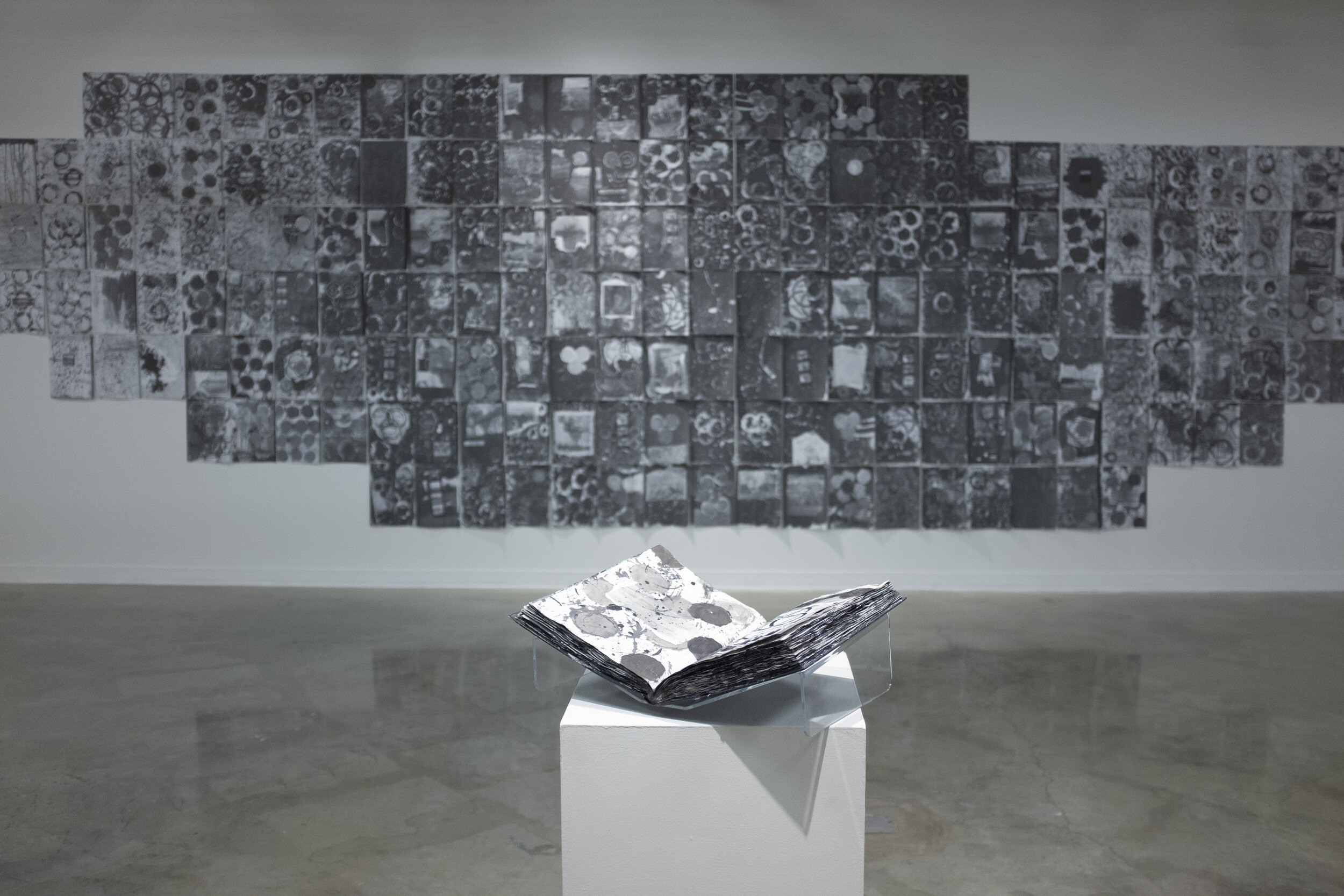

A 196-page mixed-media sketchbook with hundreds of original medium format and 35mm photographs, images dowloaded from the internet, and black and white acrylic paint.

On the wall: The 196 pages, plus the covers and insides of the book scanned and printed on copy paper.

Video

Video, mixed-media, field recordings, sounds from the vinyl record and looped melodies, drones and altered sounds using a modular synthesizer.

Useless Bodies

“As soon as this scene is no longer haunted by its actors and their fantasies, as soon as behavior is crystallized on certain screens and operational terminals, what’s left appears only as a large useless body, deserted and condemned. The real itself appears as a large useless body.”

“The Ecstasy of Communication,” Jean Baudrillard, 1987

Photographs of found shopping carts taken at night, in and around Annandale, and along Route 1, in Virginia. Nine images, each 16.5 x 12 inches, inkjet prints, 2020.

Further reading:

It’s 1 to 495 to 236 to 244, cloverleaf interchanges and driving just under the speed limit.

Then dozens of Central American men dot the vast parking lot as pickup trucks troll the strip mall’s service road looking for day laborers. The intermittent “Open” neon sign on the top window of a massage parlor in an office park. The small stand-alone house in the middle of a parking lot, a former record store that also sold bong and pipes and other paraphernalia. The boarded-up building where I took my first electric bass lessons. The abandoned antique store where boys perused the hundreds of vintage issues of Playboy under the watchful eye of the shopkeeper. The metal beams on the upper corner of a hollowed out once-bustling department store, like the collarbone of a naked shoulder. The road with almost the same name as the guitarist of the Manchester band we used to worship. Housing developments named after vestiges of the deciduous forests and animals that once covered and inhabited the Eastern half of North America. The eternal luminous bloom of yellow and orange and red fast-food restaurants and gas station signs. The distant crackle of drive-through window chatter. Hundreds of seagulls parked on acres of asphalt beaches dotted with puddles from a recent rain. A crow eats roadkill.

At a supermarket I buy a sealed plastic container with chunks of pineapple or sometimes watermelon because I remember how much she liked to eat it ice cold, sharing with one of the beagles we had. Other times I buy oranges or peaches or pears or whichever fruit is in season.

Once in the parking lot of the nursing home I turn off the concerned voices of the public radio in-depth analysis show. No more opinions or ideas or points of view or considerations or both sides of both sides.

I sit in silence.

I think about reports of a newly discovered island in a lake on an island in a lake on an island and I try to see how many iterations of an island in a lake on an island in a lake on an island I can imagine into in infinity until I lose count. I look up and the white moon in the blue sky reminds me how for the last 4.5 billion years it has been drifting away from Earth at a rate of 3.8 centimeters every year and I increase its size until I can almost touch it. I see free divers taking deep breaths and slowing their heartbeats in preparation to set new depth world records. I wonder about looking at Vantablack, the blackest material developed so far.

In the guestbook I write down the exact time of my arrival and her name in the here to see space. I get ready to start my cell phone’s stopwatch as soon as I see her to keep track of time. In front of a pair of elevators I wait for the doors of the working one to open. The other one has been out of service for more than a year. I look at the dusty pardon our dust sign. It is only one floor up but I have already set off the alarm once trying to get out of the stairwells on the other side of the building.

On the slow ride up I read the badly photocopied calendar of events and remembrances with a black and white faded photo of a recently deceased movie star behind clear plastic on the elevator wall.

The elevator doors open on her floor and many pairs of vacant eyes lift up from dilapidated bodies in wheel chairs. A menagerie of birds that nobody wants to exhibit anymore sent to spend their final days hidden away in storage. They size me up. Join us.

The din of televisions flows out from the many rooms along the narrow hallway. Game shows, the news, sports, commercials, old movies, the canned laughter of a sitcom. A soup of disembodied voices and music and sounds reverberating and resonating along the plastic floor tiles, along the patina of old paint, under the flickering fluorescent lights like a river of eternal ephemerality.

Now I stand still and a parade of rooms spins like a zoetrope where each slit is a door, a sliver of a room and I see the end of beds, the shapeshifting blue vapor of a television light hanging in the air and falling on the lower half of old bluish legs that don’t walk anymore and coming out from underneath ill-fitting gowns. I see withered flowers, presents, and get well and birthday cards and the calendar of events with the dead star hanging from cork boards. The gentle hand of the screen light coming from syndicated shows lifts the bodies just inches off the wrinkled sheets and holds them in suspended animation.

I smell excrement, just cleaned up, and urine, or soiled adult diapers in an unseen trash bin. I see school lunch cafeteria gelatinous and translucent brown gravy cratering the middle of mashed potatoes.

The wheel stops spinning and I am at her door. A small black silhouette with her back to me and facing the bright window. I knock on the open door and call out to her and she greets me as if we have been having an ongoing conversation, as if I had entered the apartment she used to have when she lived on her own almost four years ago. I unseal the plastic fruit bins and she devours the fresh fruit. She does not open the adult coloring books anymore. The conversations in our mother tongue with my mother that I crave have dwindled to a few strands of words that sound as distant as the wind in the trees in the park far across the street from her window.

We sit in silence for some time.

I suddenly remember that I want to hear her sing if she remembers a children’s song we used to sing and we sing:

Al crear la vaca (in creating the cow)

Dios hizo la leche (God made milk)

Hizo el dulce de leche (made dulce de leche)

Todo lo hizo bien (made everything well)

Por eso hay que cantar aleluya… (That’s why we have to sing halleluyah)

We laugh. It is summer on the beach with a hot dog and a coke in Montevideo again.

We sit in silence.

She will not remember that I came. She looks tired and sleepy. A lack of short-term memory makes for eternal days. She comes in dreams. I have seen her able to walk and talk and make sense and drive. A record that spins backwards and the grooves get unworn and the needles are pulled up and pulled out.

The virus comes and the new normal is not a shiny new normal. No more visits. We get letters that somebody inside has tested positive.

It’s 1 to 495 to 236 to 244, cloverleaf interchanges and driving just under the speed limit.

At the supermarket I buy chunks of pineapple or sometimes watermelon because I remember how much she liked to eat it ice cold, sharing with one of the beagles we had. Other times I buy oranges or peaches or pears or whichever fruit is in season.

In the new normal wayfinding there are one way arrows on the floor at the entrance of each food aisle. The distant crackle of new normal pre-recorded announcements calmly asking that we keep a new normal distance. I imagine a rectangular screen with many heads in small rectangular boxes during a remote corporate meeting that efficiently hatched this new normal care and looking out for us. I see the woman speaking above me from a far-off speaker wearing a mask as she speaks into the microphone. The takes it took her to come up with this new normal, normal voice.

Once in the parking lot of the nursing home I turn off the what could have been done, what will be done, the looking for someone to blame, the looking for those responsible.

As I approach the building, I see a blurry greenish figure dressed in what looks like a hazmat suit walks past behind the darkened glass windows of the lobby entrance. When I get closer, I can make out that the entrances of the hallways leading to other parts of the building are now sealed with transparent containment barriers with zippers.

When I drop off the bag with food, a tiny woman, also bringing food, begs the receptionist in nurse scrubs and behind a face shield, behind a mask, to make sure her mother gets the delivery. We make eye contact when she turns around and from above her mask, she makes new normal eyes to me.

Then it is my turn to ask the eyes behind the face shield, behind the mask, to please take the food to my mother, to please unseal the plastic container because her hands do not have the strength to do it and if the food is not shown to her and fed to her she will forget that it is there.

When I leave, outside, a small distance to my left, I see the same tiny woman approach a ground floor window, to her mother’s room. From inside the dark room the bright rectangle of the television pokes through the translucent shabby curtains, but she is short and cannot jump high enough to see her mother.